Twisted Incentives and Unhealthy Profits

The summer of 2018 offered some captivating headlines. Starbucks gave up on straws, a watery lake was found on Mars, and Justin Bieber and Hailey Baldwin secretly married in a NYC courthouse. In less popular news, the notorious chemical company Monsanto faced its first jury trial in corporate history.

Apocalyptic wildfire smoke ironically ensconced San Francisco as the first of the Monsanto Roundup cancer trials was underway. Plaintiff Lee Johnson’s legal team hustled to prove to the jury that exposure to the herbicide Roundup had caused his Non Hodgkin’s Lymphoma.

The pharmaceutical giant Bayer spent $63 billion to acquire Monsanto just as the trial began, showing no evidence of concern that the cancer litigation – eventually stacking up to over 100,000 plaintiffs and billions of dollars in settlements – would hinder what they considered to be a strategic expansion of their existing agriculture business. Meanwhile, onlookers wondered why a respected brand like Bayer would be interested in acquiring the most hated company in the world.

While reasons for the acquisition are manifold, Bayer sought to become less reliant on its pharmaceuticals business and augment its existing genetically-modified seed portfolio. Monsanto’s shares were trading at a discount due to a global slump in commodity prices and a failed attempt to acquire Swiss rival Syngenta. Bayer gambled that combining its fungicides, herbicides, and insecticides with Monsanto’s seed strength and digital farming platform would help to feed the planet. Or at least pad their wallets.

With proper due diligence prior to the transaction, this acquisition never would have been funded. Instead, Credit Suisse successfully executed equity and debt issues, including overbooked, multi-tranche US and European bond offerings. Apparently, no one bothered to Google “glyphosate”, or they would have found the reports that the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) found glyphosate to be a “probable human carcinogen.” They also would have seen litigation on behalf of cancer-ridden plaintiffs was well underway.

Between the date of the Monsanto acquisition (June 7, 2018) and the third cancer lawsuit verdict against Bayer (May 13, 2019), the Bayer stock price plummeted from $29.42 to $15.91, a drop of over 45%. Today, following several more recent verdicts for the plaintiffs, Bayer’s stock price is even more dismal at $8.42.

At the 2020 JP Morgan Healthcare Investment Conference, I watched Stefan Oelrich, Head of Bayer Pharmaceuticals, nonchalantly claim that the Roundup litigation was a “strange animal” because there was no proof that Roundup causes cancer and it was still allowed to be sold to consumers. He also wisely made clear that he was not personally involved in pursuing the Monsanto acquisition.

The Monsanto acquisition was arguably the worst acquisition in corporate history – a well-deserved barb not only for its massive destruction in shareholder value, but also for the impact of its portfolio of toxic chemicals and pesticide-tolerant seeds on human health and that of the planet at large.

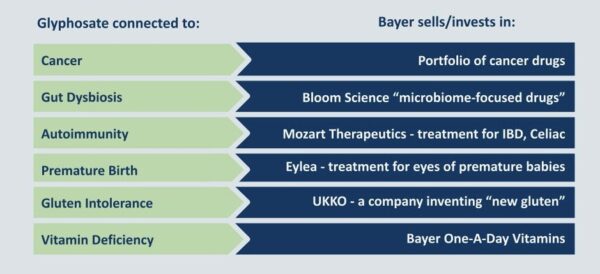

The acquisition also raised a greater ethical question as to whether a pharmaceutical company should control the food supply. This combination creates a questionable incentive system in which Bayer benefits by feeding consumers food that keeps them sick.

If human exposure to the chemicals Bayer sells contributes to the development of cancer, food sensitivities, autoimmunity, microbiome disturbances, and vitamin deficiency, should the company be legally allowed to sell cancer therapies, autoimmune treatments, probiotics, and multivitamins? Bayer both causes and treats the diseases, and profits at each end. The FTC might not have a regulatory precedent for this uniquely unethical business plan – equivalent to the merger of a pharmaceutical company and big tobacco.

Despite its brilliant business plan in which Bayer profits from making people sick with their own toxic products, there are murmurs of imminent change in its corporate structure. Bayer CEO Bill Anderson, who replaced the mastermind of the Monsanto acquisition Werner Baumann, announced last month that Bayer is considering a separation of the agricultural business in order to focus on “what’s essential for [Bayer’s] mission.”

As legacy Monsanto litigation continues to drain Bayer’s coffers, separation is likely the only feasible strategy that will allow Bayer to cushion its messy financial and ethical downward spiral. The remarkable lessons from this business case will linger in M&A finance and corporate social responsibility (CSR) classes for decades.